I want to write down some thoughts about the relation between the sublime and catastrophe that struck me when reading Kant’s Critique of Judgement last year. While reading, I kept looking for ways to make his argument fruitful for thinking about ecological catastrophe. That quest seemed justified firstly by the fact that Kant himself uses natural phenomena as his primary examples of sublime things, and secondly by the fact that the

sublime refers to experiences that surpass our ability to grasp them through our

senses or our understanding – and that, surely, is an important quality

of many catastrophes.

I will first present what I see as the (provocative) core of Kant's argument, namely that natural forces that appear to overwhelm us can give us pleasure since they confirm the superiority of reason. I will then argue that his analysis can be made fruitful for thinking about ecological catastrophes, but only if we drop his assumption that sublimity can only be appreciated from a contemplative standpoint where we don't need to fear for our safety. I will also underpin my argument by briefly discussing how the concept of the sublime relates to history, morality and feelings such as grief and humliation.

Reason and the pleasure of the sublime

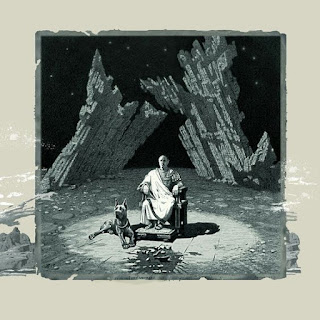

First, here is how Kant describes the experience of the sublime. It's a vivid description that brings out how pleasurable this experience can be.

[C]onsider bold, overhanging and, as it were, threatening rocks,

thunderclouds piling up in the sky and moving about accompanied by lightning

and thunderclaps, volcanoes with all their destructive power, hurricanes with

all the devastation they leave behind, the boundless ocean heaved up, the high

waterfall of a mighty river, and so on. Compared to the might of any of these,

our ability to resist becomes an insignificant trifle. Yet the sight of them

becomes all the more attractive the more fearful it is, provided we are in a

safe place. And we like to call these objects sublime because they raise the soul's

fortitude above its usual middle range and allow us to discover in ourselves an

ability to resist which is of a quite different kind, and which gives us the

courage [to believe] that we could be a match for nature's seeming

omnipotence. (Kant 1987[1790]: 120)

Kant contrasts the sublime with the beautiful. The sublime, like the beautiful, is pleasing. But while beauty relates to the object's form, the sublime is connected to formlessness and unboundedness. Unlike the beautiful, the sublime is not playful and not compatible with charms. It not only attracts but also repels the mind, meaning that the pleasure of the sublime is a "negative pleasure" (ibid. 98f). Rather than with lawful movement, it is "in its chaos that nature most arouses our ideas of the sublime, or in its wildest and most ruleless disarray and devastation" (ibid. 99f). More specifically, "nature is sublime in those of its appearances whose intuition carries with it the idea of their infinity" (ibid. 112).

But how can something that humiliates the mind's powers of understanding give rise to a feeling of pleasure? Kant's answer is stimulatng but provocative: while the sublime (unlike beauty) exceeds our sensibility and understanding, our very ability to feel it confirms reason's superiority over nature. This is because the capacity of thinking it requires a

faculty in the human mind that is itself supersensible.

If the human mind is nonetheless to be able even to

think the given infinite without contradiction, it must have within itself

a power that is supersensible [...]. For only by means of this power and its idea do we, in

a pure intellectual estimation of magnitude, comprehend the infinite in the

world of sense entirely under a concept (ibid. 111f)

Our appreciation of the sublime in nature is similar to how, in mathematics, the mind masters phenomena that exceed our capability of sensation, such as the infinite, by forming concepts about them. The pleasure in regard to the sublime thus arises from the superiority of reason over the faculty of sensibility. While for the imagination, the sublime appears "like an abyss" in which it fears to lose itself, for "reason's idea of the supersensible" it is "not excessive but conforms to reason's law to give rise to such striving by the imagination" (ibid. 115).

Kant's solution to the riddle of why the sublime can be pleasurable rests on his division of the mind in two faculties, understanding and reason, where the former refers to judgements about the empirical world (as we experience it through our senses) while the latter refers to the power of inference (which is not limited by our senses). Whereas the beautiful refers us to understanding, the sublime refers us to reason. This explains why the sublime both attracts and repels. While humiliating our senses and our understanding, it "is at the same time also a pleasure, aroused by the fact that this very judgment, namely, that even the greatest power of sensibility is inadequate, is [itself) in harmony with rational ideas" (ibid. 115). Or more concisely: “Sublime is what even to be able to think proves that the mind has a power surpassing any standard of sense” (ibid. 106).

Indeed, who would want to call sublime such things as shapeless mountain masses piled on one another in wild disarray, with their pyramids of ice, or the gloomy raging sea? But the mind feels elevated in its own judgment of itself when it contemplates these without concern for their form and abandons itself to the imagination and to a reason that has come to be connected with it - though quite without a determinate purpose, and merely expanding it - and finds all the might of the imagination still inadequate to reason's ideas. (ibid. 113)

Thus

any spectator who beholds massive mountains climbing skyward, deep gorges with

raging streams in them, wastelands lying in deep shadow and inviting melancholy

meditation, and so on is indeed seized by amazement bordering on terror,

by horror and a sacred thrill; but, since he knows he is safe, this is not actual

fear: it is merely our attempt to incur it with our imagination, in order that

we may feel that very power's might and connect the mental agitation this

arouses with the mind's state of rest. In this way we [feel] our superiority to

nature within ourselves, and hence also to nature outside us insofar as it can

influence our feeling of well-being (ibid. 129)

Imagination figures in two roles here. In its first, it makes us see our dependence on physical things. But the sublime gives it a new role, namely "to assert our independence of natural influences, to degrade as small what is large according to the imagination in its first [role]" (ibid. 129).

The extent of Kant's provocativeness should be clear by now. Today, the environmental movement has taught us to be wary of Enlightenment reason and its belittlement of nature, but his argument unabashedly aims at driving home how triflingly little nature means in producing the sensation of the sublime. To Kant, the awe that sublime natural phenomena evoke is actually a disguised awe for the ability of our own reason to elevate us above the violent natural forces. Indeed, he goes out of his way to argue that it is actually the mind that is sublime, rather than the natural objects themselves (ibid. 105).

Hence the feeling of the sublime in nature is respect for our own vocation. But by a certain subreption (in which respect for the object is substituted for respect for the idea of humanity within our[selves, as] subject[s)) this respect is accorded an object of nature that, as it were, makes intuitable for us the superiority of the rational vocation of our cognitive powers over the greatest power of sensibility (ibid. 114)

Hence sublimity is contained not in any thing of nature, but only in our mind, insofar as we can become conscious of our superiority to nature within us, and thereby also to nature outside us (as far as it influences us). Whatever arouses this feeling in us, and this includes the might of nature that challenges our forces, is then (althougb improperly) called sublime. (ibid. 123)

So: the sublime humiliates part of us (understanding and sensibility, the part of us that is tied to our status as empirical beings) but at the same time elevates another part (reason, our capacity to think independently of the senses). A surprising volte-face has occurred: the tremendous might of nature only serves to fuel the pleasurable sensation of reason's superiority to the senses. In worshipping storms and mountains we worship reason. Instead of elevating the object, the sublime elevates the subject.

Isn't this hubris?

But what is this, we may ask, if not blatant, unabashed idealism? Isn't it precisely the kind of hubris that the environmental movement has warned us against - the hubris of a reason conceited enought to congratulate itself for its superiority to nature? As usual, Kant defends himself well. He himself takes up the objection that it is presumptuous to claim superiority for reason. Isn't the proper attitude to the sublime, he asks, one that should be borrowed from the religious attitude to God, an attitude of prostration, submission, and humility?

[I]n tempests, storms, earthquakes,

and so on [...] we usually present God as showing himself in his wrath but also in

his sublimity, while yet it would be both foolish and sacrilegious to imagine

that our mind is superior to the effects produced by such a might [...]. It seems that here the mental attunement

that befits the manifestation of such an object is not a feeling of the

sublimity of our own nature, but rather submission, prostration, and a feeling

of our utter impotence [...]. It seems that in religion in general the

only fitting behavior in the presence of the deity is prostration, worship with

bowed head and accompanied by contrite and timorous gestures and voice; and

that is why most peoples have in fact adopted this behavior and still engage in

it. (ibid. 122)

Here it is easy to associate with today's ideas of the wrath or revenge of nature and the environmentalist call for humility and contrition. Kant's counterargument, however, is that contrition and fear of punishment is not intrinsically connected with sublimity.

A person who is actually afraid and finds

cause for this in himself because he is conscious that with his reprehensible

attitude he offends against a might whose will is at once irresistible and just

is not at all in the frame of mind [needed] to admire divine greatness, which

requires that we be attuned to quiet contemplation and that our judgment be

completely free. (ibid. 122)

In the same way, we cannot appreciate the sublime in nature if we are afraid. "For we flee from the sight of an object that scares us, and it is impossible to like terror that we take seriously" (ibid. 120). Kant, then, defends himself by claiming that our appreciation of the sublime never rests on real fear. It always presupposes a "safe place" from which we, as spectators, can contemplate the forces of nature. Just as we only appreciate beauty when we approach it in a contemplative frame of mind - without "interest", as he puts it - so we only appreciate the sublime when we are safe from danger.

This argument may sound plausible, but it raises questions. Is it true that we don't appreciate the sublime in moments of thrilling risk and danger? Aren't those the moments when we, in fact, have the strongest and most intense experiences of the sublime? To the extent that "being safe from danger" is part of Kant's definition of the sublime, it is of course impossible to refute him. One can argue, however, about whether it is an appropriae and fruitful definition. What reasons did Kant have for making it and are those reasons sound?

I can't see that Kant had any good reasons for limiting the sublime to what we can experience in a contemplative state of mind from a "safe place". I even believe that it goes against the overall thrust of his more important argument about how the sublime proves the superiority of reason. To put it in a nutshell, if reason can only prove its superiority when we are in a "safe place", then it doesn't really prove its superiority at all. A reason that needs physical security to operate is hardly superior to natural forces. In other words, whereas Kant usually talks about "us" as beings capable of reason, here he suddenly - and unwarrantedly, I believe - slips into an identification with mere understanding.

Instead of arguing that sublimity requires an absence of physical danger, wouldn't Kant have been more consistent if he had argued that reason is always in a "safe place" simply by virtue of being reason? That, I believe, would have been in keeping with his overall theoretical edifice, in which the distinction between nature and freedom is fundamental. Nature is defined by causal relations grasped theoretically by understanding, while freedom is grasped practically by reason. Reason operates by principles belonging to a supersensible realm that cannot be reduced to nature. The mere presence of physical danger should not be able to threaten the integrity of reason, since reason is defined by its capacity to operate in a supersensible realm, regardless of whether our physical bodies are safe from danger or not.

My view is therefore that the assumption that the sublime requires a contemplative attitude can be dropped without hurting the overall thrust of Kant's argument. Dropping it would allow for the possibility of experiencing the sublime even in the midst of catastrophes and moments of great danger. Above, I raised the question whether risks can enhance the feeling of sublimity. Isn't it indeed precisely in the ability to enjoy danger and overcome fear that reason's superiority is shown most clearly? Isn't there even an art of creating or inviting sublimity by playing with risks, as suggested by examples such as mountain climbing, drugs and gambling? If we allow for the idea of sublime courage, which I think we should (and here Kant seems to agree, as seen in his discussion about the veneration for soldiers, ibid. 122), then the idea that sublimity requires physical safety must surely be dropped. Rather than interpreting Kant as claiming that sublimity requires a safe standpoint where we don't need to feel fear, I prefer to interpret him as saying that it requires an ability to overcome fear.

The latter interpretation would be in keeping with Kant's suggestion that "war" can inspire feelings of sublimity (ibid. 122). This statement is one of the rare instances where Kant finds examples of the sublime in history rather than nature. It helps us relativize the distinction between history and nature which is otherwise a recurring feature of his thinking. Formlessness, excess and violence exist not only in nature but of course also in history, where they are manifested in an endless series of catastrophes, shocks and traumas. Just as nature can give rise both to beauty and sublimity, one may find beauty in history (for instance by its aesthetization in the form of narratives) as well as sublimity, as for instance in the fortitude and spiritual strength that allow people to rise after a crushing defeat or catastrophe.

Let us return to the objection about humility. My point is not that feelings of utter impotence, fear, contrition and humliation should be made part of the concept of the sublime. I believe that Kant is right that that would be to stretch the concept too far - but right for the wrong reasons. It is not because the sublime requires a contemplative stance or a safe distance that he is right, but simply because such feelings are not a necessary part of the concept of the sublime. The sublime, I suggest, does not require a "safe place" and, contrary to what Kant suggests, it is eminently compatible with feelings of fear, humiliation and so on. It is thus not the absence of such feelings - or the absence of physical dangers that might produce them - that defines the sublime, but the ability to overcome them and rise above them. This overcoming is made possible not by physical safety, but by a shift from the standpoint of understanding to the standpoint of reason. From the standpoint of understanding, we view ourselves as natural beings subjected to the causality nexus of the empirical world. From the standpoint of reason, we view ourselves as free beings capable of thinking and acting independently of that causal nexus.

Kant as environmentalist

Following my critical remarks above, I will now defend Kant. The interpretation I suggested above should, I believe, make his position more palatable to environmentalists. In particular it should make it easier to rebut the objection that it represents Enlightenment hubris and insensitivity to nature. Despite his provocative idea that the pleasure of the sublime derives from a realization of reason's superiority over nature, there is little of hubris in this idea. As physical beings and as creatures of understanding we are subjected to nature and other causal forces around us. It is only as rational beings that we have a chance of rising above those forces. The sense of superiority obtained in sublime moments cannot be taken for granted, but is an uncertain and perhaps fleeting achievement that requires us to overcome feelings such as fear and humiliation. Furthermore, this superiority does not connote any actual physical mastery over nature or any other parts of the empirical world, but is at best a mental mastery, an inellectual relief or satisfaction that at least our capacity as free and rational beings is still unharmed by the violent and formless forces around us. This is well expressed in the following passage:

[T]hough the irresistibility of nature's might makes us, considered as natural beings, recognize our physical impotence, it reveals in us at the same time an ability to judge ourselves independent of nature, and reveals in us a superiority over nature that is the basis of a self-preservation quite different in kind from the one that can be assailed and endangered by nature outside us. This keeps the humanity in our person from being degraded, even though a human being would have to succumb to that dominance [of nature]. Hence if in judging nature aesthetically we call it sublime, we do so not because nature arouses fear, but because it calls forth our strength [...] to regard as small the [objects] of our [natural] concerns: property, health, and life (ibid. 120f)

I would have preferred to write that nature, in sublime moments,

both arouses fear

and calls forth the strength to overcome fear. But apart from that, I think that this passage dovetails nicely with what many environmentalists are saying. Kant is clear about the fact that nature can be a source of catastrophes, of immense devastation concerning human life, goods and health. The affinity to environemtalism is even more evident regarding how we should respond to the present ecological crisis. The predominant call of environmentalism today is that we should wake up to our responsibility to act as free and rational beings. We need to rise to the occasion and exercise our freedom by breaking out of the passivity of our ordinary routines. In other words, we need to prove the superiority of our reason by breaking free from the seemingly inexorable causal forces driving us towards doom.*

Kant presents the sublime as an eye-opener that can help us achieve this intellectual awakening, a reminder of our capability to act as free and rational beings even when we are confronted with catastrophes so immense that they appear to surpass understanding. That a link exists between sublimity and action is shown by the fact that sublime moments always include such a reminder, unlike moments of beauty which we can enjoy as contemplative spectators. What we enjoy in sublime moments is not so much the self-congratualitory sense of the superiority of reason per se, as its link to the freedom that we can discover within ourselves even in the most difficult circumstances.

Should we really aestheticize catastrophes?

We can now turn to a common objection to applying the concept of sublimity to catastrophes. The argument is that it is inappropriate and frivolous to apply such a concept to catastrophes since it turns them into aestheticized objects of pleasure. Here, for instance, is the philosopher Günther Anders, writing on the topic of nuclear apocalypse:

I am explicitly avoiding the term ‘the sublime’ here, which Kant uses in The Critique of Judgment to name that which exceeds all proportiones humanas, all ‘human proportions’. […] The instant of the nuclear flash, the view of the annihilated city of Hiroshima, and the prospect of its inevitable repeat are anything but ‘grandiose’ or ‘sublime’. (Anders 2019: 140 n1)

But this objection seems more pertinent to the attempt to find

beauty in catastrophes. Regarding the sublime, however, I think that two points can be made that show that it doesn't necessarily involve any frivolity or making light of suffering.

Firstly, unlike beauty, the sublime reminds us of our responsiblity to act as moral, free beings. The pleasure that accompanies it does not disregard suffering. On the contrary, it is a pleasure we feel when we are able to rise to the occasion and act as free and rational beings despite the adverse circumstances. This is not so different from when the eco-philosopher Joanna Macy asserts that even if the future looks bleak, we can still think: “How lucky we are to be alive now—that we can measure up in this way”.

Secondly, although it may seem self-evident it deserves to be pointed out that the sublime doesn't exhaust our possible reactions to catastrophe. Far more common is simply pain, grief and despair. There's nothing sublime or pleasurable about such experiences, which capture the devastating and traumatic impact of catastrophes. It is not catastrophe per se that is pleasurable but our (rarely exercised ) ability to respond to it as free and morally responsible beings, using our faculty of reason. This is also why feelings such as grief or fear should be conceptually distinguished from the sublime. They differ from the sublime, not because we are not in a "safe place" when we feel them, but because the sublime is defined by the ability to rise above such feelings.

This second point also points to the limits of using the concept of the sublime for understanding our reactions to catastrophes. While it is useful for theorizing a certain response to catastrophes, to many people such a response will not be possible. It presupposes a subject that remains intact, despite the catastrophe. But traumatized people cannot be expected to elevate themselves over the catastrophe. Nor is there any moral obligation that they should do so. No one can tell a person to stop grieving. Grief can, however, be a step towards recovery. The idea of rising after a defeat hints at the fact that sublimity may be the result of a process that requires time and in which feelings of grief, impotence and humliation may be central ingredients. Such feelings are not sublime in themselves, but they are not incompatible with sublimity. As Kant points out, humility can coexist with sublimity to the extent that it is guided by reason: “Even humility… is a sublime mental attunement, namely voluntary subjection of ourselves to the pain of self-reprimand so as gradually to eradicate the cause of these defects” (ibid. 123). This is echoed in the environmentalist call for contrition, which can be seen as a call to human beings to reflect on and atone for the wrongs they have committed against nature. That sublimity can coexist with feelings of this kind is not surprising, considering that we are creatues both of understanding and reason. Kant's argument in nuce is that what humiliates the former provides an opportunity for elevating the latter.

Is the concept of the sublime useful for thinking catastrophes?

As physical beings, we are vulnerable to the might and violence of forces that can destroy our lives, our health, our property, and all the things that we cherish. But sublime moments make us see these things as "small", thereby reminding us that we are also rational beings, partaking in the supersensible realm of freedom. This is the core of Kant's argument. It is not an idea of reason's ability to subjugate nature materially. Instead, it accepts the tremendous force of nature in the realm of materiality, but asserts that all is not lost when this material realm is shattered in catastrophe.

So can Kant's concept of the sublime be made fruitful for thinking about enviornmental catastrophe? The answer is yes, but only if parts of his argument are modified. Firstly, more than Kant we probably need to pay attention to history as an arena of the sublime next to nature. After all, history has a far greater role in producing the natural phenomena that could be seen as sublime than in Kant's days, and the same can be said of the repercussions of environmental destruction on history in the form of a catastrophes. Secondly, we must drop his assumption that the sublime can only be appreciated from a "safe place", as contemplative spectators. In today's ecological catastrophe, no such safe place exists. Thirdly, we probably need to emphasize more than he did that sublimity is an uncertain achievement. Most catastrophes wil simply produce pain, grief, fear and traumatization rather than sublimity. But despite this, the idea of the sublime may well be indispensible for thinking about catastrophes since it indicates the possibility of eye-opening experiences that awakens us to freedom and moral responsibility.

References

Anders, Günther (2019) “Language and End Time (Sections I, IV and V of ’Sprache und Entzeit’)” (tr. Christopher John Müller), Thesis Eleven 153(1): 134-140.

Hamilton, Clive (2017) Defiant Earth: The Fate of Humans in the Anthropocene, Cambridge Polity Press.

Kant, Immanuel (1987[1790]) The Critique of Judgement (tr. Werner S. Pluhar), Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Co.

Macy, Joanna (2014) “It Looks Bleak. Big Deal, It Looks Bleak”, Exopermaculture.com, posted on April 2 2014 by Ann Kreilkamp; https://www.exopermaculture.com/2014/04/02/joanna-macy-on-how-to-prepare-internally-for-whatever-comes-next/ (accessed 2021-02-06).

Sloterdijk, Peter (1987) Critique of Cynical Reason, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

* This is of course an extremely common exhortation among environmentalists. An eloquent example is Hamilton (2017). Outside of environmentalism, Sloterdijk (1987: 130ff) expresses a similar idea in his idea of the bomb as the Buddha of the West.