I recently reread Mikhail Bulgakov's The Master and Margarita (Penguin 2016), which I read for the first time in high school. What impressed me most that time was the brooding, unhappy figure of Pilate. He who longs for nothing more than to meet Yeshua Ha-Notsri again, the mad philosopher who had made the outrageous claim that all people were good and whom he had sentenced to death. I've never forgotten Pilate's dream, in which the two of them are reunited and happily walk along a moonlit path, discussing endlessly with each other.

They were arguing about something very complex and important, and neither of them could refute the other. They did not agree with each other in anything, and that made their argument especially interesting and endless. (p. 319)

To me this is a glorious picture of happiness.

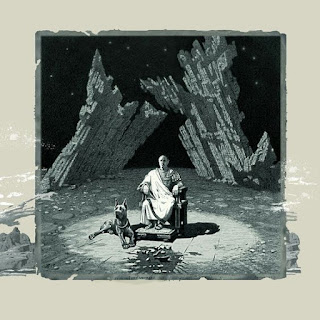

|

| Vyacheslav Zhelvakov, illustration for The Master and Margarita (Pilate) |

I still love the Pilate chapters for their dark, psychological portrait of a tormented man, but this time I found myself much more drawn to the parts of the book in which Woland (Satan) and his clownish-sinister entourage take centre stage. The chapters on the meeting by the Patriarch Pond and the late-night talk in Satan's room after the great ball are especially delightful - partly because they're funny and partly because they're so rich in interpretative possibilties.

While reading I couldn't help thinking of Stalin and the oppressive circumstances under which Bulgakov was working in the 1930s. Especially in the early part of the novel, I felt that Stalin was everywhere - in the ’mysterious disappearances’ from Apartment No. 50 in chapter 7 (which made me recall the many sudden "disappearances" in the 1930s which Robert Conquest describes in The Great Terror); in Ivan’s "splitting in two" in chapter 11 (which made me recall the absurd conversions displayed at show trials), and so on. By explaining these phenomena not by Stalinist terror but by black magic, Bulgakov satirically turns Stalin into a devil and life in the Soviet Union into a realm of the supernatural. Laughter becomes serious, a refusal to accept the forgetfulness of God in a totalitarian system (I write "God" here, but "conscience" might work just as well). As the translator writes in his introduction, the subversive nature of laughter in Bulgakov's novel hints a a kinship with Bakhtin. I imagine that the freedom, laughter and happiness in the atmosphere surrounding Woland must have been a mental breath of fresh air - a force for sanity even - to Bulgakov in the maddening circumstances in which he was writing. The novel's two famous catchphrases - "manuscripts don't burn" and "cowardice is the most terrible of vices" - acquire their subversive radiance precisely against the background of repression. So does the statement, often repeated in the novel, that Moscow has been invaded by "unclean powers". Didn't Bulgakov sneak in those words at least in part for the sheer pleasure of being able to utter them in the midst of a totalitarian society, even while pretending to speak of Woland?

Let me try to develop my interpretation a bit. To see clearer how the novel makes sense of this totalitarian background, I think Greimas and his semiotic square can be helpful.

The idea I want to try out here is that the relation between courage and power is the novel's central theme, or at least that they are fundamental to its "meaning universe". That cowardice is the worst of vices is repeated several times in the novel, most memorably by Yeshua on the cross (p. 305). According to a footnote by the translator, Bulgakov also told a friend that cowardice was the worst of vices "because all the rest come from it" (quoted on p. 410 n7). As for power, it is a pervasive presence in the relations depicted in the novel. For instance, an enormous asymmetry of power is the most striking feature of Satan's and Pilate's relations to others around them.

Lets see where the novel's characters can be mapped onto the square. Margarita is courage at its purest. Throughout the second half of the novel, she is a truly glorious and delightful heroine. Although a bit nervous at first - and who wouldn't be when faced with the devil? - she soon learns to face all dangers in high spirits, including Woland himself who even pays homage to her for her courage - "That's the way!", he joyfully exclaims (p. 282).

Margarita's courage is married to love, but not to power. In this, she is like the innocent and naive Yeshua, whose fate lies in Pilate's hands, but who despite this refuses to bow to his power and who remains full of concern for others even while suffering on the cross. While lacking power, both Margarita and Yeshus possess the courage not to give up their love. There's not a trace of cowardice in either. To be sure, their fates are different. Margarita's final triumph contrasts with Yeshua's crucifixion. But their fates are not as different as it might look. Being crucified is the price paid for courage in the face of power. Metaphorically, crucifixion is what writers such as the master and Bulgakov himself had to face for producing works that were unpalatable to the authorities. Having chosen life with the master, Margarita would have faced crucifixion herself if it hadn't been for Woland's helping hand. Although she achieves "peace" for herself and the master at the end, it is significant that it is not in this world that this final triumph becomes possible, but - just as in Yeshua's case - in a beyond.

Incidentally, the parallel between Margarita and Yeshua is underscored by the similar lines they use to comfort the ones they have saved. Thus Yeshua tells Pilate, in the latter's dream, that "[n]ow we shall always be together" (p. 320), and Margarita says to the Master, as Satan finally grants them peace: "And you will no longer be able to drive me away. I will watch over your sleep" (p. 384).

The prime representative of cowardice is my old favourite character Pilate. He shows why courage is so important to Bulgakov. Courage is needed in a totalitarian system to escape perdition. Or perhaps one should say: to avoid becoming part of the general badness of any society (including those societies in which we, the readers, happen to live). Pilate's fault was precisely that the lacked the courage to follow his conscience. As he explains, how could he, the procurator of Judea, "ruin his career" for the sake of a mad philosopher (p. 320)? The opportunists of the literary establishment who attacked the master and drove him to insanity are like tinier versions of Pilate, unable to ruin their careers by behaving decently. Just as Margarita och Yeshua combine courage and powerlessness, Pilate and the literary vultures combine cowardice and power. The result is corruption, a corrupt, evil power that kills the best in its possessors and that turns into a trap since they lack the courage to give it up.

The opposite of power - powerlessness - is best represented by the master, who lets himself be defeated and broken by the literatuy establishment. Losing belief in his novel and in himself, he escapes into self-chosen confinement in a mental ward. Unlike Margarita and Yeashua, he lacks not only power but also courage (by combining the two negatives, he represents what Greimas called the "neutral term"). It is clear, I think, that he also represents a predicament experienced by the masses, the common people in a repressive society, who need to act cowardly to survive. In the novel, people like Annushka, the secret informer Aloisy Mogarych and the tenant association chairman Bosoy seem like good examples of this. The nameless master may of course also represent some part of Bulgakov himself.

Somewhat surprisingly, the utopian possibilities generated by the novel's semiotic universe find their outlet in the dark prince, "messire" Woland, who incarnates the "complex term" that combines the two positives, courage and power. Not only is he nearly all-powerful ("Nothing is hard for me to do", p. 361), he is also clearly not a coward. We know that from Milton, of course ("And courage never to submit or yield / And what is else not to be overcome?", as the spiteful Lucifer exclaims on Mount Niphrates). Yes, there is much of Milton's Satan in Woland (Bulgakov refers to Goethe's Mephisto in his epigraph but Woland is not just a simple reiteration of Mephisto, who lacks Woland's grandeur and munificence). Woland is a prince and a rebel, a despiser of cowardliness (recall how contemptuously he refers to Matthew as a "slave", ibid.). Importantly, he is a force of subversion of the powers that be and thereforce also a source of hope.

If I'm right then Woland is an "imaginary solution to a real contradiction", as Fredric Jameson put it - a utopian projection of the longing for a synthesis of good things that are hard to reconcile in reality. That he is a projection is shown by his ambiguity: he is both the evil of this world and the one who redeems us from it, Stalinist terror and the one who saves us from Stalin. It is in order to resolve the theological nicities of this paradox that Bulgakov refers to Mephisto, the spirit that "wills evil and eternally works good", but that reference seems to me to be very much like a smoke screen: clearly much of the havoc that Woland wreaks on Moscow is good in itself, a sort of liberating destruction. The true evil, by contrast, is the deadening hand of the status quo, the falsity and general badness of the system as it is. This evil has little or nothing to do with Woland and is instead represented by the neutral term, a society in which people can only survive by becoming "cowards". Not even those who possess power within this fallen society are free, but, like Pilate, trapped by it. Courage is also of little use, unless supernatural forces lend a helping hand. So the people awaits a powerful, courageous, and non-existent savior.

|

| Marcin Minor, illustration for The Master and Margarita (Behemot) |